The views and opinions expressed in this Blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent.

It is a notorious fact that implementing in practical terms complex, multi-faceted concepts such as “digital sovereignty” is not always an easy task. We live in a complicated world, and the European tech sector and its supply chains have become an increasingly intricate amalgam of global relations, many of them based on deep asymmetric dependencies that are nowadays quite impossible to reduce overnight. But sometimes miracles happen and destiny offers you a unique opportunity to define a clear path towards Europe’s strategic autonomy. This is currently the case with AI Factories.

“In the first 100 days, we will ensure access to new, tailored supercomputing capacity for AI start-ups and industry through an AI Factories initiative.”

Political Guidelines for the next European Commission 2024−2029

Ursula von der Leyen (18/07/2024)

In 2024, the Council of the EU amended the Regulation of the EuroHPC Joint Undertaking to allow this public-private initiative to establish and manage AI Factories across Europe. EuroHPC is an entity created in 2018 that has traditionally been focused on strengthening the EU’s supercomputing capabilities. HPC has always been crucial to the scientific community and for product innovation in a number of strategic sectors such as automotive, pharma, and aerospace. This amendment was part of the EU’s broader AI innovation package, and its main objective was to make it much easier for public and private users with AI needs (especially European start-ups and SMEs) to get access to the expensive and large-scale resources that only AI-optimised supercomputers can offer when it comes to executing compute-intensive tasks like the training and development of general-purpose AI models.

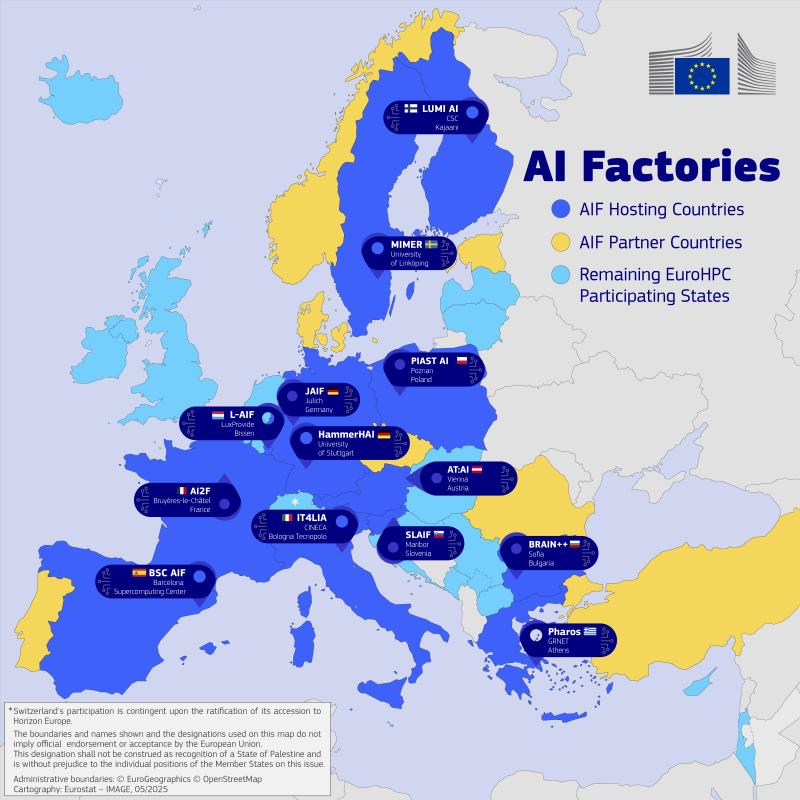

In September 2024, EuroHPC launched two calls for EOIs to start identifying entities that were interested in hosting and operating an AI Factory. The expectation has always been that many of the organisations already hosting a EuroHPC supercomputer would submit an application to get additional funding for upgrading their existing facilities with AI capabilities. For that, applicants had to show their commitment not only to mobilising additional hardware resources but also to integrating cloud software tools, delivering training, and providing user support. In December, the European Commission announced that EuroHPC had selected the first seven AI Factories, with a second announcement coming in March 2025 and involving another six additional AI Factories. As reported by the EC, these first two rounds of AI Factories represent a total investment of near 2 billion EUR, combining national and EU funding.

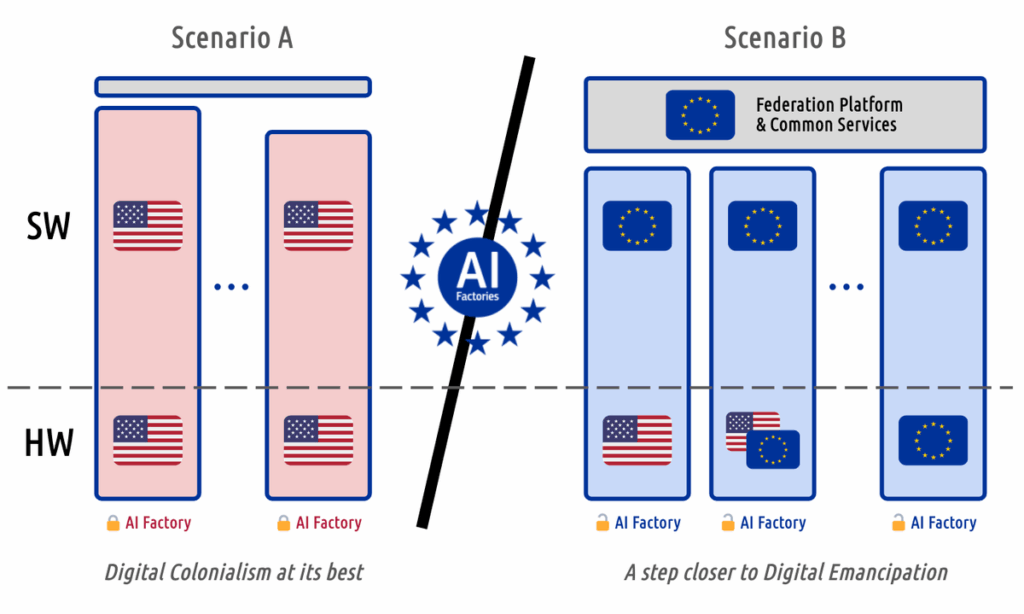

Such a significant investment has, obviously, attracted the interest of Big Tech and US software vendors, always eager to exploit Europe’s fragmentation and industrial dependencies—especially at the hardware level. Many AI Factories are being approached as we speak and tempted to adopt the end-to-end software solutions that some of those non-EU vendors have put together. To their prospective customers they are promising a pretty user interface and a tight integration with the underlying hardware, a fast deployment—so that AI Factories can show that they are finally delivering on the EC’s promise—and grandiloquent corporate press releases that will ensure that their new ‘shiny objects’ are featured in the media.

What’s the catch? Most of those AI platforms are based on proprietary components fully controlled by US vendors, establishing a strong vendor lock-in that makes AI Factories completely dependent on a non-EU technological stack and impossible to interoperate. This is the dream of the Trump administration, which has already expressed openly its intention to exploit the strong dependencies at the lowest levels of the AI infrastructure (i.e. chips & accelerators) in order to force the global adoption of an “American AI Technology Stack”. At the moment, some European AI Factories run the risk of becoming early adopters of that stack—motu proprio!

But, is there an alternative? The answer is: there must be. First thing AI Factories need to do is to make sure that they adopt a European open source software stack to manage their new AI infrastructure and its associated cloud services. The main objective here is to provide a sovereign hardware abstraction layer that decouples Europe’s strategic AI capabilities from vendor-locked ecosystems and the proprietary frameworks that non-EU software providers and some integrators are right now trying to position at the core of our AI Factories. Middleware components such as compilers and SDKs, orchestration tools, inference and training runtimes, model catalogues, and cloud services must be able to run across heterogeneous hardware environments.

AI Factories must allow European developers and companies to build, train, and deploy AI models using a unified software interface, but avoiding a scenario in which those 2 billion EUR in public funding lead to further dependencies with Big Tech and with foreign governments. This sovereign software approach can accelerate adoption by startups and SMEs by leveraging existing hardware platforms from NVIDIA and AMD, while keeping control over data management, AI model execution, and governance. But, more importantly, this is really the only way for protecting the possibility of a future migration to European hardware.

The managers of the new AI Factories must think strategically, and resist the temptation of looking only for quick solutions for their most immediate challenges. Beyond current expectations, AI Factories will have a key role to play in a few years’ time, when EU-designed AI hardware—including CPUs, GPUs, and NPUs—become broadly available in the market. These components “made in Europe” will have to be gradually integrated into the existing HPC and AI cloud infrastructures if we really want Europe to ever regain its strategic autonomy in the digital world. This can only happen if AI Factories adopt now a sovereign software approach offering hardware abstraction and technical interoperability.

That is the basic step that will allow us in the future to bring together all the different pieces in which the EU has been investing thousands of millions from taxpayers’ money, including the several IPCEIs in Microelectronics, the open source solutions for AI that we are developing under the IPCEI Cloud (i.e. Fact8ra.AI), the Chips Joint Undertaking, the European Processor Initiative, or the DARE project on RISC-V. Otherwise, EU citizens and businesses will be right to ask their institutions and political representatives why on earth, despite all previous efforts and upcoming multi-billion initiatives like the AI Gigafactories or the new IPCEI on Artificial Intelligence, we keep putting our critical digital infrastructure in the hands of Big Tech corporations.

Alberto has developed most of his career in Spain and in the UK, both in Tech and in Academia. As VP of Open Source Innovation at OpenNebula Systems, he deals with strategic collaborations with cloud and edge providers, other open source initiatives, and CIOs from relevant vendors. Alberto coordinates the SovereignEdge.EU initiative and is involved in the European Alliance for Industrial Data, Edge and Cloud, where he supports the role of OpenNebula Systems as chairing company of the Cloud/Edge Working Group while co-leading its Open Source Task Force. In March 2024, Alberto was elected Chair of the Industry Facilitation Group of the new €3B IPCEI Cloud, where he also coordinates the ♾️ Fact8ra.AI initiative—the transversal integration pilot that is creating the first multi-tenant AI-as-a-Service platform based on European open source technologies.

0 Comments