The views and opinions expressed in this Blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent.

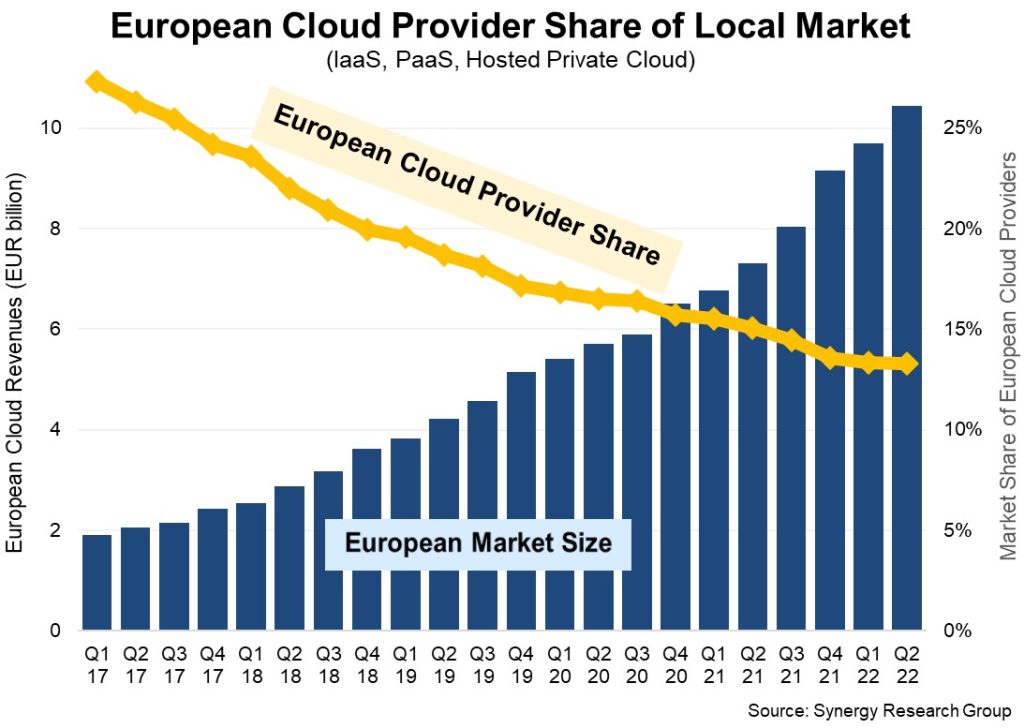

It is a well-known fact that the European cloud computing sector is struggling to match demand and provide a genuine alternative to global competition from hyperscalers. According to a recent analysis that includes IaaS, PaaS, and hosted private cloud services, the European cloud market, which was worth 10.4 billion € during the second quarter of 2022, has grown tremendously over the past five years and is now five times bigger than it was back in 2017. However, the collective market share of the European players has shrunk dramatically from 27% to a mere 13%.

The global public cloud market is converging very rapidly around three large US providers—namely Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud—with no EU cloud provider coming even remotely close to being able to challenge their leadership in the European market either. Currently, the strongest European cloud players are SAP and Deutsche Telekom (each of them with a mere 2% of the European market share), followed by others like OVHcloud, Telecom Italia, and Orange.

According to Eurostat, 41% of the enterprises in the EU use the cloud, with 73% of them declaring themselves to be highly dependent on cloud computing. What this represents is, in practice, an increasingly large dependency on non-EU cloud service providers, something that raises serious concerns about personal data protection, cybersecurity, or applicable legislation. EU authorities are perfectly aware of this strategic vulnerability, and there are in fact great expectations about the potential of the emerging edge computing paradigm to help bring some balance to a market whose rapid growth in Europe during the COVID times is merely consolidating an existing oligopolistic structure dominated by powerful non-EU corporations.

As highlighted in the European Data Strategy, the volume of data our societies generate is increasing very rapidly and, by 2025, 80% of all that data is expected to be processed at the edge, closer to end-users and IoT devices. Both the EU’s New Industrial Strategy and the 2030 Digital Compass emphasize the need to leverage the current tendency towards decentralized multi-provider edge cloud infrastructures to open up the data economy, regain autonomy in a market dominated by non-EU providers, and ensure that European rules and values are respected. By 2030, for instance, the plan is to have at least 10,000 climate-neutral, highly secure edge nodes available in the EU. It is by leading the deployment, management, and commercialization of this critical new edge infrastructure that European companies will finally position themselves as a competitive alternative to hyperscalers.

This changing scenario is putting additional pressure on the EU telecom industry, a sector already struggling in its relationship with Big Tech. Telcos are now also expected to play a key role in the deployment of that future edge cloud infrastructure, leveraging their 5G networks and on-the-ground presence across Europe. Surprisingly, despite the huge potential of this new market, some of them are still sticking to expensive, non-EU proprietary platforms like VMware, or even helping hyperscalers (e.g. through programs like AWS Wavelength) launch their first commercial edge deployments in Europe. This approach creates unsustainable dependencies, weakens their own position in the value chain, and relegates them to the position of irrelevant, co-location providers. Luckily, more and more EU telcos are starting to see those agreements as the ‘Trojan horses’ they really are.

From Data Sovereignty to Technological Sovereignty

Digital sovereignty has been at the heart of public debate in the EU for a while now, becoming an integral element of what has been described as “the birth of geopolitical Europe”. As EC President Ursula von der Leyen herself stated a few years ago, “it may be too late to replicate hyperscalers, but it is not too late to achieve technological sovereignty in some critical technology areas”, supporting the idea that “we must have mastery and ownership of key technologies in Europe”. Europe cannot make its digital and green transition happen without establishing technological sovereignty. Europeans must strengthen their mutual collaboration in areas of strategic importance such as defense, aerospace, and pharma, but also around crucial technologies such as 5G/6G, semiconductors, hydrogen, and quantum computing.

Everyone agrees that cloud and edge computing are also key enabling technologies of strategic importance for Europe in order to achieve the much-needed digital transformation of businesses and the public sector. Cloud and edge computing are crucial for an interconnected, cohesive, and resilient digital Europe, as well as for the EU’s geostrategic position and competitiveness in the global economy. Yet cloud sovereignty cannot be achieved without strengthening Europe’s capacity to control not only that new edge cloud infrastructure, but also the software technologies that allow organizations to securely combine their on-premise resources with the emerging multi-provider cloud-edge continuum. The EU has to develop and protect these critical edge cloud management platforms because the only possible alternative to that scenario would be to simply leave the technological foundations of the EU’s data economy in the hands of non-EU software vendors.

Several EU initiatives are starting to show Europe’s practical aspirations to boost its home-grown technologies and digital capabilities so that the current, disproportionate exposure to non-EU vendors and cloud providers can be reduced. Two of the main instruments for achieving those objectives are the European Alliance for Industrial Data, Edge and Cloud and the IPCEI on Next Generation Cloud Infrastructure and Services (IPCEI-CEI). The EU Cloud Alliance is bringing together businesses, EU member states, and relevant experts to jointly define the strategic investment roadmap that will enable the next generation of cloud and edge computing technologies. On the other hand, the IPCEI-CIS aims at creating the common capabilities and edge cloud infrastructures that Europe needs, along with advanced data processing services able to leverage the emerging datacenter-edge-cloud continuum.

While European technological companies are still learning how to navigate the new geopolitical context, US vendors of proprietary cloud management platforms are trying hard to promote themselves in Europe as perfectly valid options for building sovereign clouds. Some of the most blatant examples of this adaptive positioning strategy come from initiatives like VMware’s Sovereign Cloud or Microsoft’s European Cloud Alliance. Although under certain conditions these vendors could indeed manage to meet some basic data sovereignty requirements, they are obviously not a valid choice when it comes to building Europe’s technological sovereignty beyond the data layer. The situation is unfortunately the same with a number of well-known open source software products.

Addressing the Complexities of the Open Source Industry

As Commissioner Thierry Breton has pointed out, “in the digital decade, Open Source will be a key element to achieve Europe’s resilience and digital sovereignty”. Open source helps to reduce the market entry barriers and improve cost, increasing market competition and technology neutrality. According to the Open Source Software Strategy 2020-2023 and the 2021 study on the impact of open source on the EU economy, open source minimizes vendor lock-in and gives Europe a chance to create and maintain its own, independent digital approach and to stay in control of its processes, information, and technology, fostering an open ecosystem around sustainable joint innovation. However, Europe can accomplish its digital independence only as long as its industry assumes an active role in developing the open source technologies that a next-generation edge cloud requires.

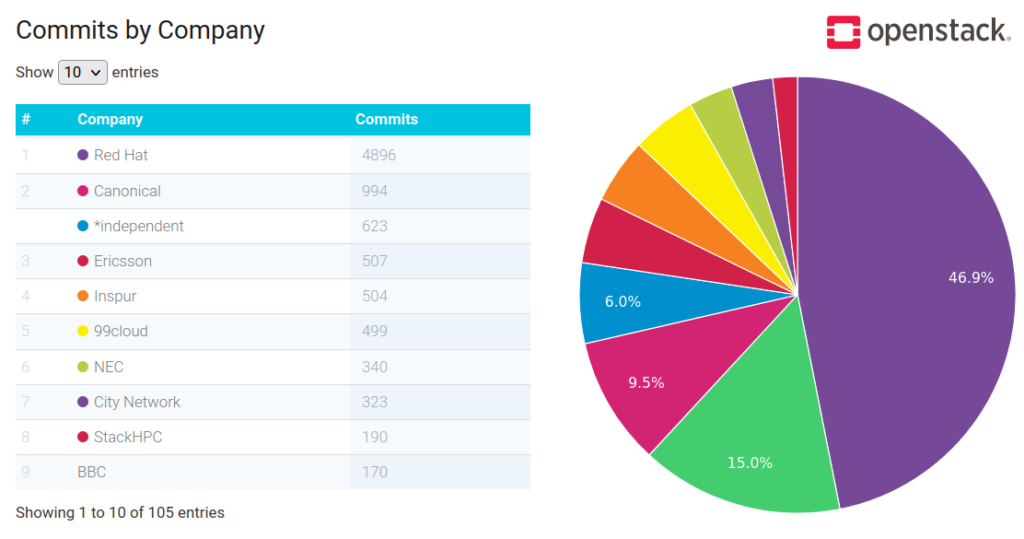

Those familiar with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy will know that “things are not always what they seem”. In fact, nowadays most of the open source technologies used to build cloud services are controlled by non-EU entities. One illustrative example is OpenStack, a hyped open source cloud management platform that is widely used by European telcos and also by web giants in emerging tech economies like China. By looking at the top 10 contributors to its latest release, for example, one can easily observe that the few EU companies in that list play only a very marginal role, with a clear majority of contributions coming from RedHat/IBM and other non-EU technology vendors. SUSE already decided to drop its whole OpenStack business line some years ago, so it comes as no surprise either that only five out of 27 members of the Board of Directors of the (Texas-based) OpenInfra Foundation actually come from EU organizations.

To position OpenStack at the core of Europe’s next-generation edge cloud and Data Spaces infrastructure would create a new series of strong technological dependencies for the EU. No matter how many large European companies have been building their products and services on top of OpenStack (or even funding their contributions to the project through EU research, development, and innovation programs), the reality is that, far from offering a ‘fast track’ for strengthening Europe’s capabilities and digital sovereignty, OpenStack has become just another extremely complex software product controlled by non-EU corporations. As sad as it sounds, no European organization would have the capacity to maintain a project fork in the long term, should those non-EU vendors decide to turn their backs on OpenStack overnight.

After the recent announcement of a future European Sovereignty Fund, it is clear now that the European Union is on a path to strengthening its geopolitical and industrial position in the world. One basic requirement of that strategy is to minimize the risks associated with the overdependence on non-EU cloud providers and technology vendors. In the process of creating a powerful innovation ecosystem around a European sovereign edge cloud, open source is destined to play a vital role. It is only through open collaboration that we can bring the EU industry together to develop the next generation of cloud and edge capacities and the technical skills that European organizations so desperately need.

Like in other strategic areas, it is time for the EU tech sector to start fighting its own digital “Stockholm syndrome” and to offer a coordinated response to some of the major challenges that Europe is facing. A necessary step will be to acknowledge the many ways in which Big Tech has gradually colonized the open source world over the last couple of decades, and the role it plays in some major cloud computing projects. The EU industry has to address this vulnerability and get ready to step in to develop and sustain together the European open source alternatives that Europe needs for reclaiming its technological sovereignty.

Alberto has developed most of his career in Spain and in the UK, both in Tech and in Academia. As VP of Open Source Innovation at OpenNebula Systems, he deals with strategic collaborations with cloud and edge providers, other open source initiatives, and CIOs from relevant vendors. Alberto coordinates the SovereignEdge.EU initiative and is involved in the European Alliance for Industrial Data, Edge and Cloud, where he supports the role of OpenNebula Systems as chairing company of the Cloud/Edge Working Group while co-leading its Open Source Task Force. In March 2024, Alberto was elected Chair of the Industry Facilitation Group of the new €3B IPCEI Cloud, where he also coordinates the ♾️ Fact8ra.AI initiative—the transversal integration pilot that is creating the first multi-tenant AI-as-a-Service platform based on European open source technologies.

0 Comments